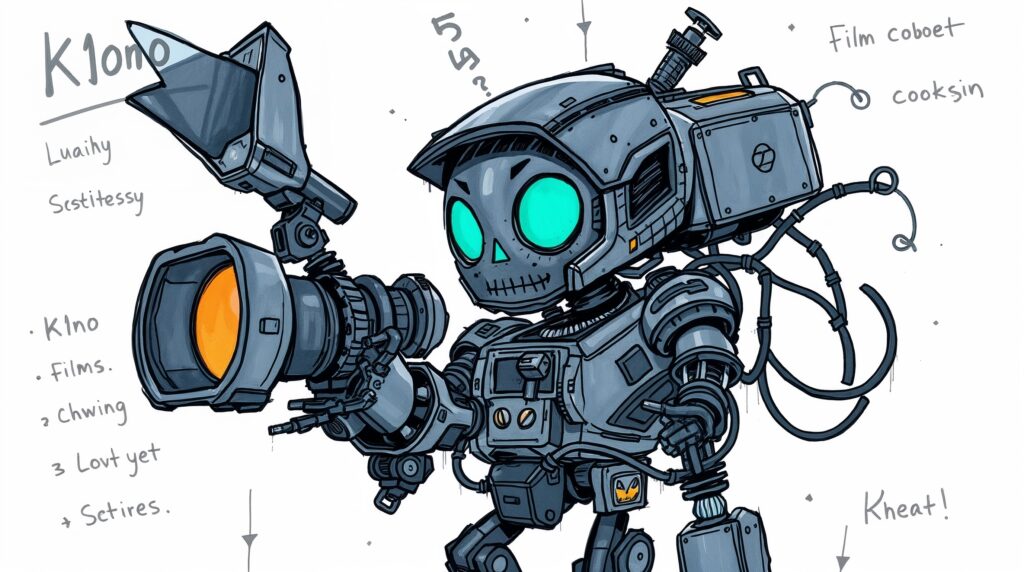

Image generated by Leonardo.Ai, 14 October 2025; prompt by me.

Notes from a GenAI Filmmaking Sprint

AI video swarms the internet. It’s been around for nearly as long as AI-generated images, however its recent leaps and bounds in terms of realism, efficiency, and continuity have made it a desirable medium for content farmers, slop-slingers, and experimentalists. That said, there are those who are deploying the newer tools to hint at new forms of media, narrative, and experience.

I was recently approached by the Disrupt AI Film Festival, which will run in Melbourne in November. As well as micro and short works (up to 3 mins and 3-15 mins respectively), they also have a student category in need of submissions. So over the last few weeks I organised a GenAI filmmaking Sprint at RMIT University last Friday. Leonardo.Ai was generous enough to donate a bunch of credits for us to play with, and also beamed in to give us a masterclass in how to prompt to generate AI video for storytelling — rather than just social media slurry.

I also shared some thoughts from my research in terms of what kinds of stories or experiences work well for AI video, and also some practical insights on how to develop and ‘write’ AI films. The core of the workshop as a whole was to propose a structured approach: move from story ideas/fragments to logline, then to beat sheet, then shot list. The shot list, then, can be adapted slightly into the parlance of whatever tool you’re using to generate your images — you then end up with start frames for the AI video generator to use.

This structure from traditional filmmaking functions as a constraint. But with tools that can, in theory, make anything, constraints are needed more than ever. The results were glimpses of shots that embraced both the impossible, fantastical nature of AI video, while anchoring it with characters, direction, or a particular aesthetic.

In the workshop, I remembered moments in my studio Augmenting Creativity where students were tasked with using AI tools: particularly in the silences. Working with AI — even when it is dynamic, interesting, generative, fruitful, fun — is a solitary endeavour. AI filmmaking, too, in a sense, is a stark contrast to the hectic, chaotic, challenging, but highly dynamic and collaborative nature of real-life production. This was a reminder, and a timely one, that in teaching AI (as with any technology or tool), we must remember three turns that students must make: turn to the tool, turn to each other, turn to the class. These turns — and the attendant reflection, synthesis, and translation required with each — is where the learning and the magic happens.

This structured approach helpfully supported and reiterated some of my thoughts on the nature of AI collaboration itself. I’ve suggested previously that collaborating with AI means embracing various dynamics — agency, hallucination, recursion, fracture, ambience. This workshop moved away — notably, for me and my predilections — from glitch, from fracture or breakage and recursion. Instead, the workflow suggested a more stable, more structured, more intentional approach, with much more agency on the part of the human in the process. The ambience, too, was notable, in how much time is required for the labour of both human and machine: the former in planning, prompting, managing shots and downloaded generations; the latter in processing the prompts, generating the outputs.

What remains with me after this experience is a glimpse into creative genAI workflows that are more pragmatic, and integrated with other media and processes. Rather than, at best, unstructured open-ended ideation or, at worst, endless streams of slop, the tools produce what we require, and we use them to that end, and nothing beyond that. This might not be the radical revelation I’d hoped for, but it’s perhaps a more honest account of where AI filmmaking currently sits — somewhere between tool and medium, between constraint and possibility.