My work on and with generative AI continues apace, but I’m presently in a bit of a reflection and consolidation phase. One of the notions that’s popped up or out or through is that of generativity. Definitely not a dictionary word, but it emerged from — of all places — psychoanalysis. Specifically, it was used by a German-American psychoanalyst and artist named Erik Erikson. Erikson’s primary research focus was psychosocial development, and ‘generativity’ was the term he applied to “the concern in establishing and guiding the next generation” (source: p. 267).

My adoption of the term is in some ways adjacent, in the sense of a property of tools or systems that ‘help’ by generating choices, solutions, or possibilities. In this sense, generativity is also a practice and concept in and of itself. Generative artificial intelligence is, of course, one example of a technology possessing generativity, but I’ve also been thinking a lot about generative art (be it digital/code-based, or driven by analogue tools or naturally occurring randomness), generative design, procedural generation, mathematical/computational models of chance and probability, as well as lo-fi tools and processes: think dice, tarot cards, or roll tables in TTRPGs.

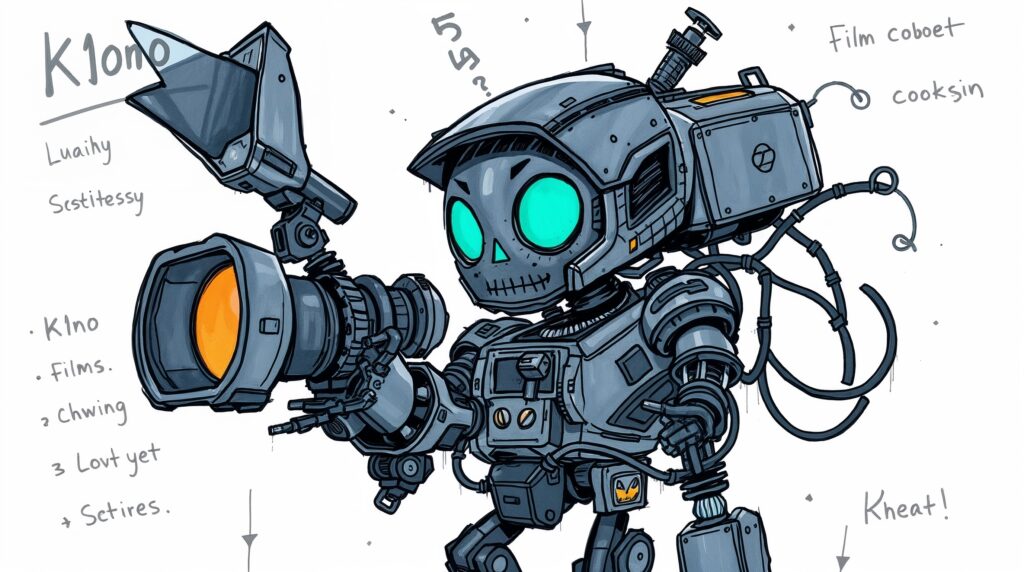

The name I’ve given my repeatable genAI experiments is ‘ritual-technic‘. These are designed specifically as recipes for generativity (one example here). Primarily, this is to allow some kind of exploration or understanding of the technology’s capabilities or limitations. They may also produce content that is useful: research fodder to unpack or analyse, or glitchy outputs that I can remix creatively. But another potential output is a protocol for generativity itself. One the one hand, these protocols can be rich in terms of understanding how LLMs conceive of creativity, human action, and the ‘real’ world. But on the other, they push users off the model, and into a generative mode themselves. These protocols are a kind of genAI costume you can put on, to try out being a generative thing yourself.

Another quality of the ritual-technic is that it will often test not just the machine, but the user. These are rituals, practices, bounded activities, that may occasion some strange feelings: uncertainty, confusion, delight, fear. These feelings shouldn’t be quashed or ignored, they should be observed, marked, noted, and tracked. Our subjective experience of using technology, particularly those like genAI that are opaque, complex, or ideologically-loaded, is the embodiment, the lived and felt experience, of our ethics and values. Many of my experiments have emerged as a way of learning about genAI in a way that feels engaging, relevant, and fun — yes! fun! what a concept! But as I’ve noted elsewhere, the feelings accompanying this work aren’t always comfortable. It’s always a reckoning: with my own creativity, capabilities, limitations, and with my willingness to accept assistance or outsource tasks to the unknown.

For Erikson, generativity was about nurturing the future. I think mine is more about figuring out what future we’re in, or what future I want to shape for myself. Part of this is finding ways to understand the systems that are influencing the world around us, and part of it is deciding when to take control, to accept control, or when to let it go. Generativity is, at least in my definition and understanding, innately about ceding some kind of control. You might be handing one of the reins to a D6 or a card draw, to a writing prompt or a creative recipe, or to a machine. In so doing, you open yourself to chance, to the unexpected, to the chaos, where fun or fear are just a coin flip away.