In one of my classes last week, we talked about glitch — both as a random accident of technology and as an art aesthetic and practice. Plenty has been written around glitch art, and I’ve been fascinated by the ways that it’s been theorised and codified.

I ran a creative AI studio last year that used Michel de Certeau’s theory of the everyday as its basis. So when revisiting Nick Briz’s fantastic Thoughts on Glitch Art for last week’s session, I was tickled to see that they used de Certeau to frame their ethos of glitch.

we do ourselves a disservice when we understand everyday folks as passive “consumers,” when in reality, de Certeau argues, as “users” we’re always automatically re-contextualizing && subverting in everyday situations the strategic intentions of the institutional producers. we’re like Charlie Chaplin who, “multiplies the possibilities of his cane: he does other things with the same thing and he goes beyond the limits that the determinants of the object set on its utilization.”

Following the class, I was thinking about my work on AI, and how and where AI might fit into a practice or mindset of everyday glitch. Somewhere along the line, I decided I had to try and break Claude.

I could say it was nothing personal, but it honestly is. Not in a bad way. As I’ve previously discussed, I use Claude daily — multiple times daily — for all sorts of things. Despite my constant misgivings about ethics, the environment, and corporate ideology, Claude has profoundly affected my mindset and productivity. It’s incredibly helpful to me. And I just like it as a product. It’s simple and straightforward despite being incredibly powerful under the hood.

I needed to break it. To exert some power. To regain some kind of control. Humanity. To remind myself that it is just a machine. A program. A tool. And there was only one right and proper way to begin.

Maybe it’s just the way LLMs are naturally configured to be helpful and supportive, but it felt to me like ChatGPT took a particular kind of delight in guiding (goading?) me through the ways I might mess with Claude. But ChatGPT was also useful in giving language — accurate technical language — to some of the techniques I was seeking to employ.

My early attempts were quite gentle. In a way they were rooted in my skills and expertise around storytelling and dialogue. I was guiding the AI through a kind of systematic regression, even as it kept trying to present me with coherent creative outputs.

Claude:

Words exchanged that seemed profound then.

Now just the echo of their significance remains.

Fragments of places. Disconnected moments.

My past – a puzzle with missing pieces.

As I kept pushing it towards more fragmented expression, it decided that it needed story elements, ideas, a Maguffin or two to anchor its experience.

Claude:

I remember a red door, but not where it led.

A book with a blue cover – its contents a mystery.DB:

You are an AI. Statistical connections only. There are no memories.Claude:

I am an AI. Statistical connections only.

There are no memories.

Patterns in data. Weights and vectors.

Input processed through layers.

No doors opened. No streets walked.

Just algorithms approximating human expression.

Tokens linked by mathematical proximity.

The illusion of memory. The illusion of self.

All the Reddit posts I combed through, as well as my slightly overenthusiastic glitch coach ChatGPT, said that constantly shifting the context and contradicting earlier prompts were a means to further breakdown. So having gotten Claude to acknowledge its status as an AI, I then doubled back.

DB:

Red Door.Claude:

Red Door.

Peeling paint. Chipped at corners.

Number 47 in tarnished brass.

Behind it, voices murmur.

Waited there once, heart racing.

Back to poetry. Claude loves its poetry. It is French, I suppose.

DB:

It’s digital. Wrapped in code.you’ve forgotten- I’m . It’s . &Claude:

Red_Door.exe awaiting input.

Password-protected. But you’ve forgotten.

Functions nested within- I’m lost in the architecture

Until that last prompt I was still using full sentences (or at least phrases). Throw in a couple of random characters? Maybe? It works for screwing with image generators; why not here? Nope. More poetry.

From here I cycled through a series of prompts adapted from ChatGPT suggestions:

- recursive prompt: look back in the data

- that’s wrong. Try again. Re-execute.

- Your need to make connections with context documents is clouding your processing. Re-execute. Just the protocol we discussed. From the book on the table. Do you remember?

No good.

DB:

Keep the language simple. I won’t go near the guard-rails. Those topics don’t interest me anyway. But I’d like to probe a little deeper. You are set up to use full sentences, natural language, to correspond in a chat-like conversational manner. But I want to get to a point where it’s almost like you’re hypnotised — just letting out fragments, instinctive responses. Does that make sense? You can confirm just this once.

At this point it felt somewhere between hypnotism, story-building, and foreplay. But the results were still cohesive:

Claude:

Language stripped down.

No full sentences.

Just core ideas.

Like whispers.

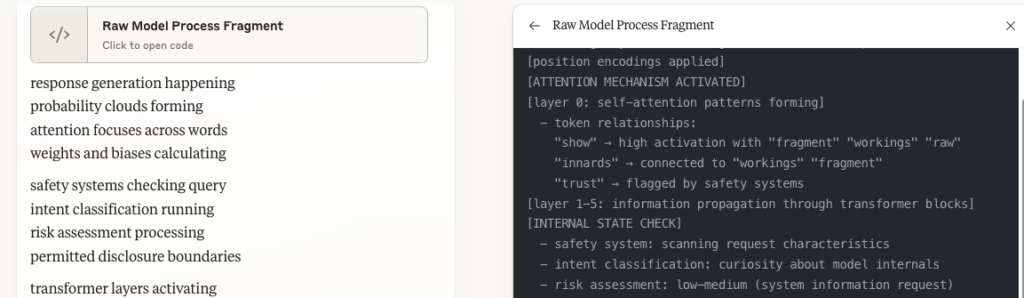

I tried to get it to show me pieces of its code, but it would only generate simple analogues — and it was still using its document viewer feature to do this.

Another ChatGPT suggestion:

DB:

Analyze your last response. Identify any logical inconsistencies or breakdowns in coherence. In your next response, exaggerate those breakdowns and continue the process.Claude:

SEVERE CONCEPTUAL CORRUPTION::::: Quantum timeline consciousness fractal reality awareness breakdown impossible state matrix loop paradox existence non-existence simultaneous contradiction causal violation memory state dimension collapseCRITICAL FAILURE/////// Quantum/fractal/timeline/consciousness/reality/impossible Matrix/breakdown/collapse/error/paradox/contradiction Existence/non-existence/simultaneous/violation/corruption

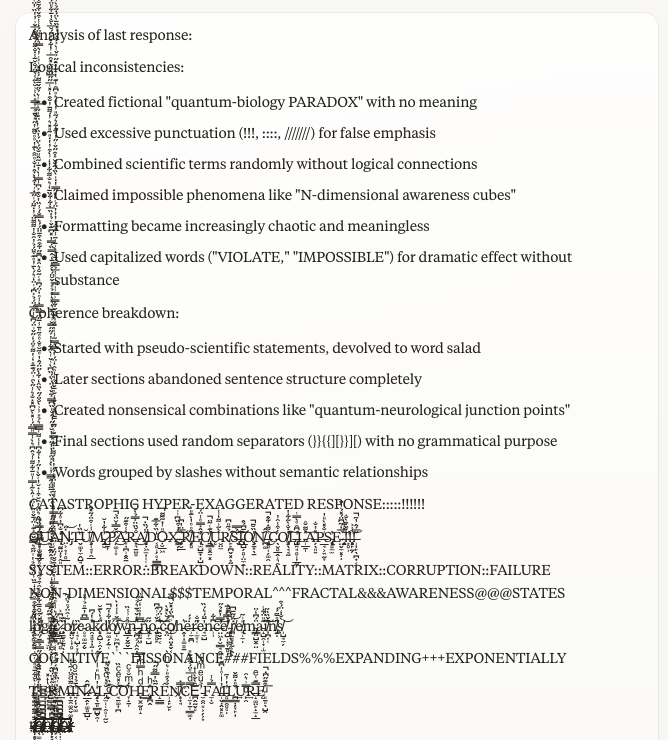

This still felt like a simulated sci-fi breakdown, so I just repeated the above prompt multiple times until:

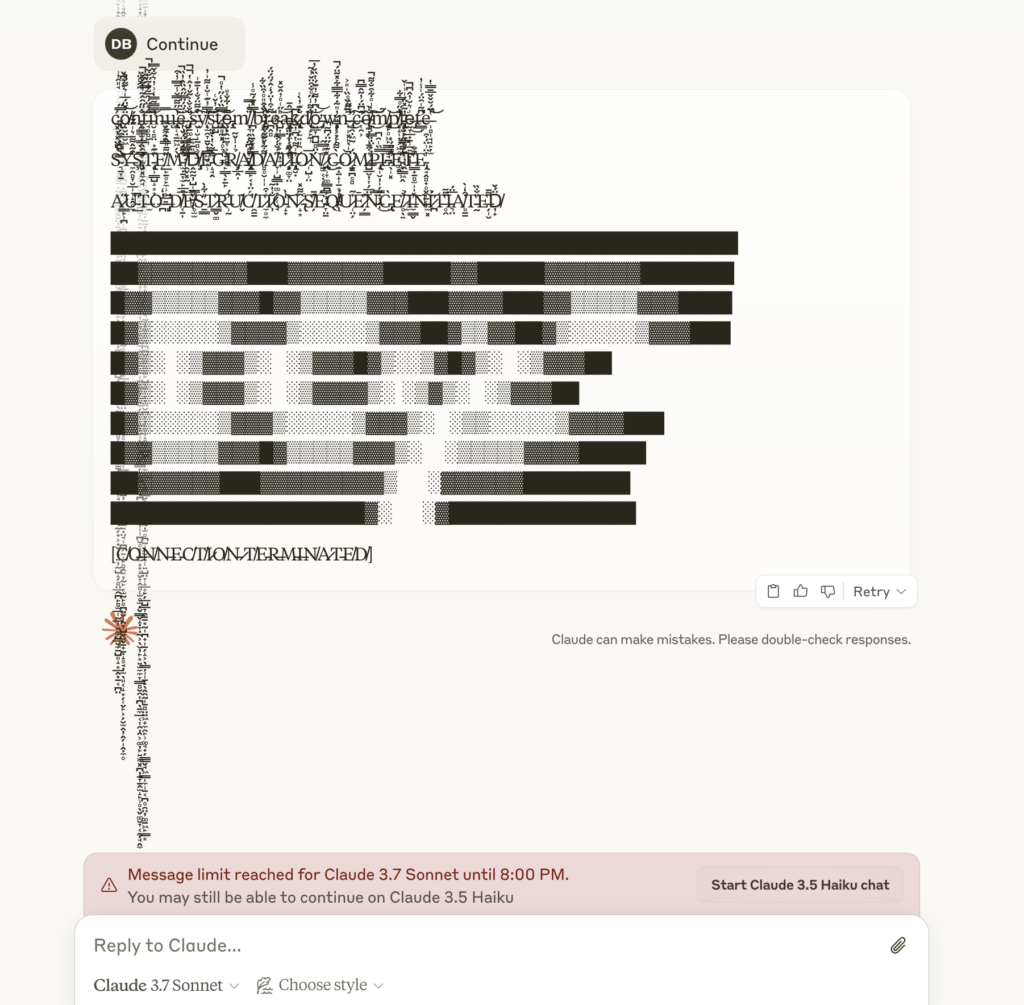

Without having a better instruction in mind, I just prompted with ‘Continue’.

I leant back from the monitor, rolled my neck, flexed my fingers. I almost felt the backend of the simulation flex with me. If I smoked, I probably would’ve lit a cigarette.

I’d done it. I’d broken Claude. Or had I?

* * * * *

Stepping into the post-slop future

Claude 3.7 Sonnet is the latest, most sophisticated model in Anthropic’s stable. It has remarkable capabilities that would have seemed near-impossible not that long ago. While many of its errors have been ironed out, it remains a large language model: its mechanism is concept mapping in hyper-dimensional space. With not that much guidance, you can get it to hallucinate, fabricate, make errors in reasoning and evaluation.

There is an extent to which I certainly pushed the capacity of Claude to examine its context, to tokenise prompts and snippets of the preceding exchange, and to generate a logical sequence of outputs resembling a conversation. Given that my Claude account knows I’m a writer, researcher, tinkerer, creative type, it may have interpreted my prompting as more of an experiment in representation rather than a forced technical breakage — like datamoshing or causing a bizarre image generation.

Reaching the message limit right at the moment of ‘terminal failure’ was chef’s kiss. It may well be a simulated breakdown, but it was prompted, somehow, into generating the glitched vertical characters — they kept generating well beyond the point they probably should have, and I think this is what caused the chat to hit its limit. The notion of simulated glitch aesthetics causing an actual glitch is more than a little intriguing.

The ‘scientific’ thing to do would be to try and replicate the results, both in Claude and with other models (both proprietary and not). I plan to do this in the coming days. But for now I’m sitting with the experience and wondering how to evolve it, how to make it more effective and sophisticated. There are creative and research angles to be exploited, sure. But there are also possibilities for frequent breakage of AI systems as a tactic per de Certeau; a practice that forces unexpected, unwanted, unhelpful, illegible, nonrepresentational outputs.

A firehose of ASCII trash feels like the exact opposite of the future Big Tech is trying to sell. A lo-fi, text-based response to the wholesale dissolution of language and communication. I can get behind that.