Read Part 1 here, and Part 2 here.

Part 3: Give me my MacBook back, Mac.

2012 was a big year. The motherland had the Olympics and Liz’s Diamond Jubilee; elsewhere, the Costa Concordia ran aground; Curiosity also made landfall, but intentionally, on Mars; and online it was nothing but Konys, Gangnam Styles and Overly Attached Girlfriends as far as the eye could see.

For me, I was well into my PhD, around the halfway mark; I’d also scaled back full-time media production work for that reason, and was picking up the odd shift at Video Ezy again. It was also the year that I upgraded to a late 2011 MacBook Pro. I think I had had one Macbook before then, possibly purchased in 2007-8; prior to this a Windows machine that was nicked from my inner west apartment around 2009, along with a lovely Sony Alpha camera (vale).

The 2011 MacBook served me well until early 2015, when I was given the first work machine, which I’m fairly sure was a late 2014 MBP. I tried to revive the 2011 machine once before, when my partner needed a laptop for study; however, when in early 2020 it took approximately 5 minutes to load a two-page PDF, we thought maybe it was time to put it away. For some reason though, I just held onto it, and it sat idle in the cupboard, until a week or two ago, when I caught myself thinking: what if…?

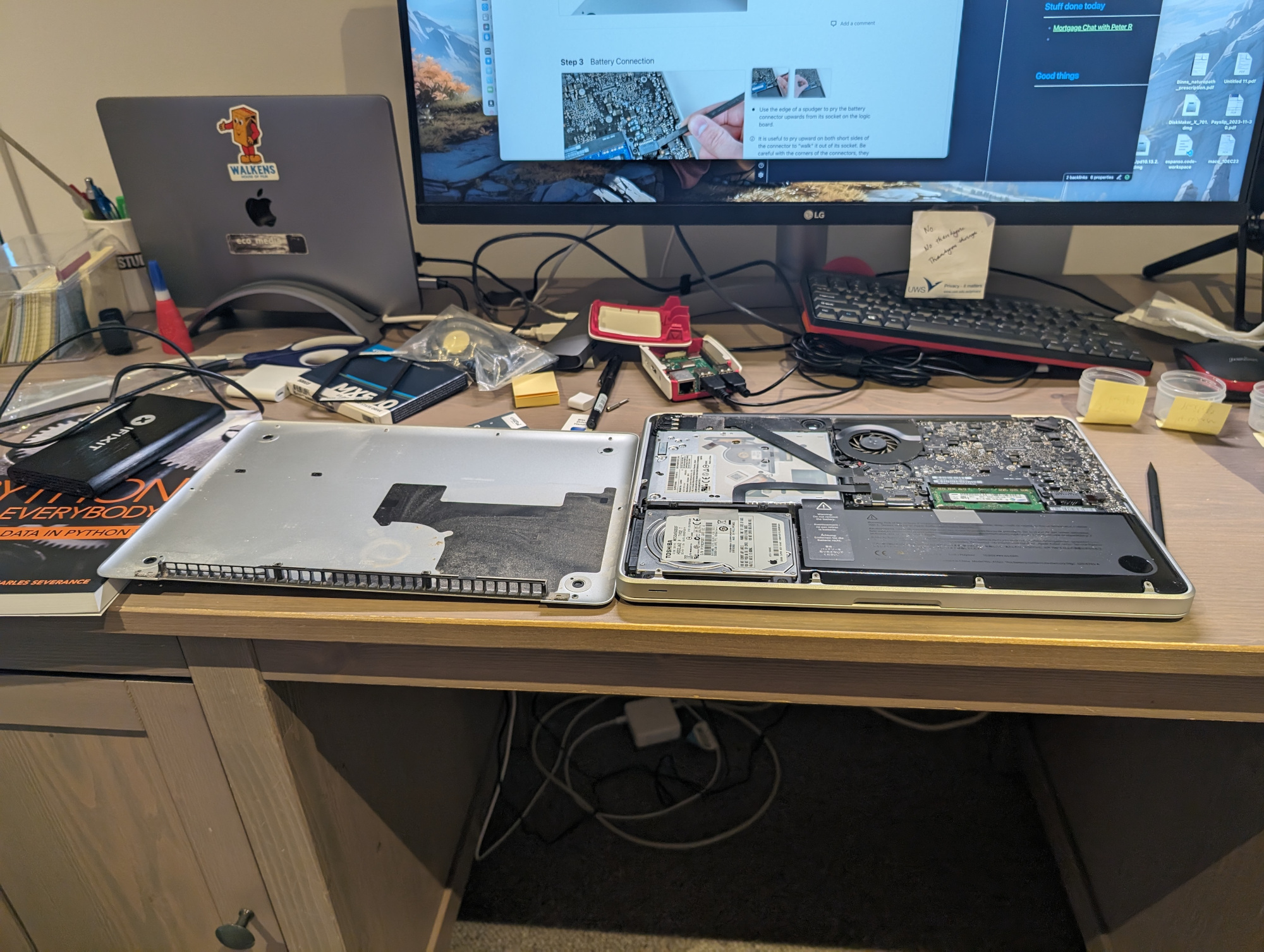

So having more or less sorted the Raspberry Pi, I turned my attention to this absolute chunkster of a laptop. It’s amazing how the sizes and shapes of tech come in and out of vogue. The 2011 MBP is obviously heavier than the work laptop, but not by as much as you’d think (2.04kg vs. 1.6kg for my 2020 M1 machine), with roughly the same screen size. Obviously, though, the older model has much thicker housing (h2.4cm w32.5cm d22.7cm vs. h1.56 w30.41 d21.24cm). Anyway, some swift searching about (by myself but mainly by my best mate, who also has huge interest in older tech, both hardware and software) led to iFixIt, where a surprisingly small amount of money resulted in an all-in-one 500GB SSD upgrade kit arriving within a few days.

I had some time to kill late last week, so I set about changing the hard drives. It was also the perfect opportunity to brush away many years of accumulated dust, and a can of compressed air took care of the trickier areas. With the help of tutorials and such, all of this took under half an hour. What filled the rest of the allotted time was sorting out boot disks for OS X. Internet Recovery was no-go at first, but with several failed attempts at downloading the appropriately agėd version, I tried once again. No good. Cue forum and Reddit diving for an hour or two, before finally obtaining what seemed to be the correct edition of High Sierra, without several probably-very-necessary security patches and so on.

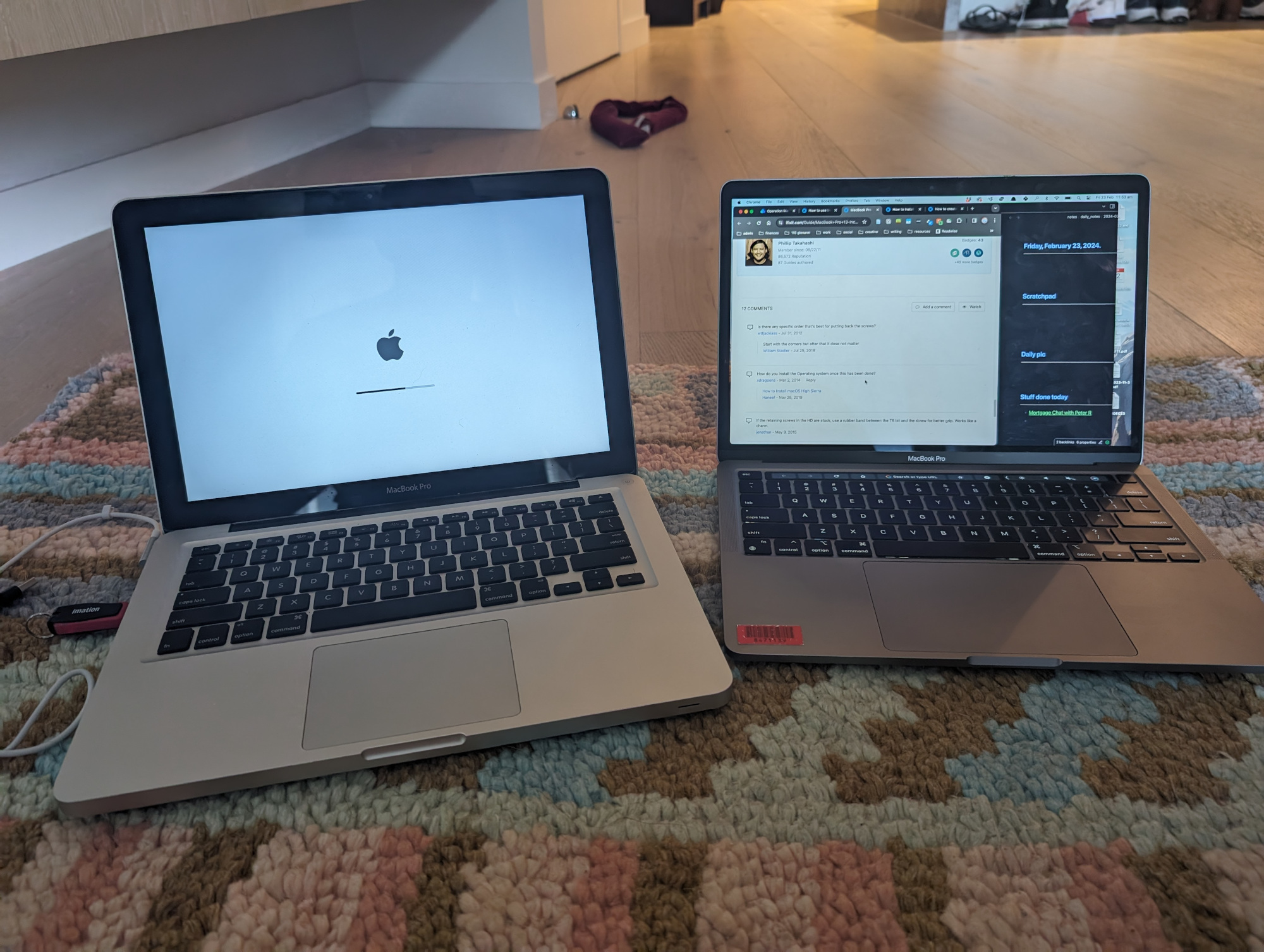

Anyway, I managed to boot up High Sierra off an ancient USB, got it installed on the SSD, and then very quickly realised that while the SSD certainly afforded greater speed than before, High Sierra was virtually unusable apart from the already installed apps and a browser. I knew I could probably try to upgrade to Mojave or maybe even Big Sur, but even with the SSD, I wasn’t sure how well it would run; and it was still tough to find usable images for those versions of macOS. But somewhere in my Reddit and forum explorations I’d seen that some had succeeded in installing Linux on their older machines, and that it had run as well and/or even better than whatever the latest macOS was that they could use.

Thanks to the Pi, I had a little familiarity with very basic Linux OS’s (aka DISTROS, yeah children I can use the LINGO I am heaps 1337); it was down to whether the MBP could run Ubuntu, or whether Mint or Elementary would be more efficient. In the end, I went with Mint, and so far so good? It’s a little laggy, particularly if multiple apps are open; I’m drafting this in Obsidian and the response isn’t great. I would also note that the systems’s fan is on, and loud, most of the time, even with mbpfan running. The resolution on my 4K monitor is worse than the Pi, of course, but this is due to the lack of direct HDMI output from the MBP; I’m using a Thunderbolt to HDMI adapter. That said, maybe I just have to tweak some settings.

In the meantime, it’s been fun to play in a new OS; Mint feels very Windows-esque, though with some features that felt very intuitive to a longer-term Mac user. Being restricted to maybe a maximum of five apps running simultaneously means I have to be conscious of what I’m doing: this actually helps me plan my workspace and my worktime more carefully. I’m using this as a personal machine, so mostly for creative writing and blogging; in general, it affords more than enough power to do a little research, take notes, draft work. If there’s anything more complex, I’ll probably have to shift to the work machine, though I did clock ShotCut and GIMP being available for basic video/image work, and obviously there’s Audacity and similar for audio.

Physically, the MBP sits flat on my desktop in front of the monitor. Eventually I will probably get a monitor arm, so it can slide back a little further. Swapping it out for my work machine isn’t too difficult; I just have to plug the HDMI into a USB-C dongle that permanently has a primary external drive, webcam and mic hooked up to it. Now that I think of it, my monitor probably has more than one HDMI input, so potentially I could just add a second HDMI cable to that arrangement and save a step. Something to try once this is posted! I’m still in a bit of cable hell, as well, due to just wanting the simplicity of plugging in a USB keyboard and mouse to the old Macbook; over the next week or two I’ll try to configure the Bluetooth accessories for bit more desktop breathing room.

Apart from these little tweaks, the only ‘major’ thing I want to tweak short-term is the Linux distro; it just feels like Mint Cinnamon may be pushing the system a little too hard. Mint does offer two lighter variants, MATE and Xfce, though I also did download Elementary and Ubuntu MATE. Mint MATE for the MBP, I reckon, and then maybe even Ubuntu MATE on the Pi. To be fair, though, most of the time the machine is struggling, I have Chrome open, so I could also just try a lighter browser, like one of your Chromiums or your Midoris.

Looking back over this drafted post, it reads like I know way more about this than I actually do. Like I’m just flashing drives and rebooting systems and slinging OS’s and SSD’s like it’s nobody’s business. To be clear: I absolutely don’t. Most of the time it was either my aforementioned best mate who knew much more about all of this stuff than I ever did, or other tech-savvy friends or colleagues; my machines have always been repaired, maintained, serviced by Mac folx, or I would just restart and hope for the best. I have a working knowledge of basic computer operation, but that barely extends to the command line, which I think I’ve used more in the last week than across my entire life. As discussed here, I don’t really code either. Most of this, for me, is just trial and error; I guess my only ‘rules’ are reading up as much as I can on what’s worked/not for other people, and trying not to take too many unnecessary risks in terms of system security or hardware tinkering. The risk in this instance is also lessened by the passing of time: warranties are well out of date and thus won’t be voided by yanking out components.

As a media/materialism scholar, I know conceptually/theoretically that sleek modern devices and the notion of ‘the cloud’ belies the awful truth about extractive practices, exploited workforces, and non-renewable materials. Reading and writing about it is one thing; to see the results of all of that very plainly laid out on your desk is quite another. One cannot ignore the reality of the tech industry and how damaging it has been and continues to be. In the same vein, though, I’m glad that these particular materials and components won’t be heading to landfills (or more hopefully, some kind of recycling centre) for a little while longer.