Some say it’s em dashes, dodgy apostrophes, or too many emoji. Others suggest that maybe the word “delve” is a chatbot’s calling card. It’s no longer the sight of morphed bodies or too many fingers, but it might be something just a little off in the background. Or video content that feels a little too real.

The markers of AI-generated media are becoming harder to spot as technology companies work to iron out the kinks in their generative artificial intelligence (AI) models.

But what if instead of trying to detect and avoid these glitches, we deliberately encouraged them instead? The flaws, failures and unexpected outputs of AI systems can reveal more about how these technologies actually work than the polished, successful outputs they produce.

When AI hallucinates, contradicts itself, or produces something beautifully broken, it reveals its training biases, decision-making processes, and the gaps between how it appears to “think” and how it actually processes information.

In my work as a researcher and educator, I’ve found that deliberately “breaking” AI – pushing it beyond its intended functions through creative misuse – offers a form of AI literacy. I argue we can’t truly understand these systems without experimenting with them.

Welcome to the Slopocene

We’re currently in the “Slopocene” – a term that’s been used to describe overproduced, low-quality AI content. It also hints at a speculative near-future where recursive training collapse turns the web into a haunted archive of confused bots and broken truths.

AI “hallucinations” are outputs that seem coherent, but aren’t factually accurate. Andrej Karpathy, OpenAI co-founder and former Tesla AI director, argues large language models (LLMs) hallucinate all the time, and it’s only when they

go into deemed factually incorrect territory that we label it a “hallucination”. It looks like a bug, but it’s just the LLM doing what it always does.

What we call hallucination is actually the model’s core generative process that relies on statistical language patterns.

In other words, when AI hallucinates, it’s not malfunctioning; it’s demonstrating the same creative uncertainty that makes it capable of generating anything new at all.

This reframing is crucial for understanding the Slopocene. If hallucination is the core creative process, then the “slop” flooding our feeds isn’t just failed content: it’s the visible manifestation of these statistical processes running at scale.

Pushing a chatbot to its limits

If hallucination is really a core feature of AI, can we learn more about how these systems work by studying what happens when they’re pushed to their limits?

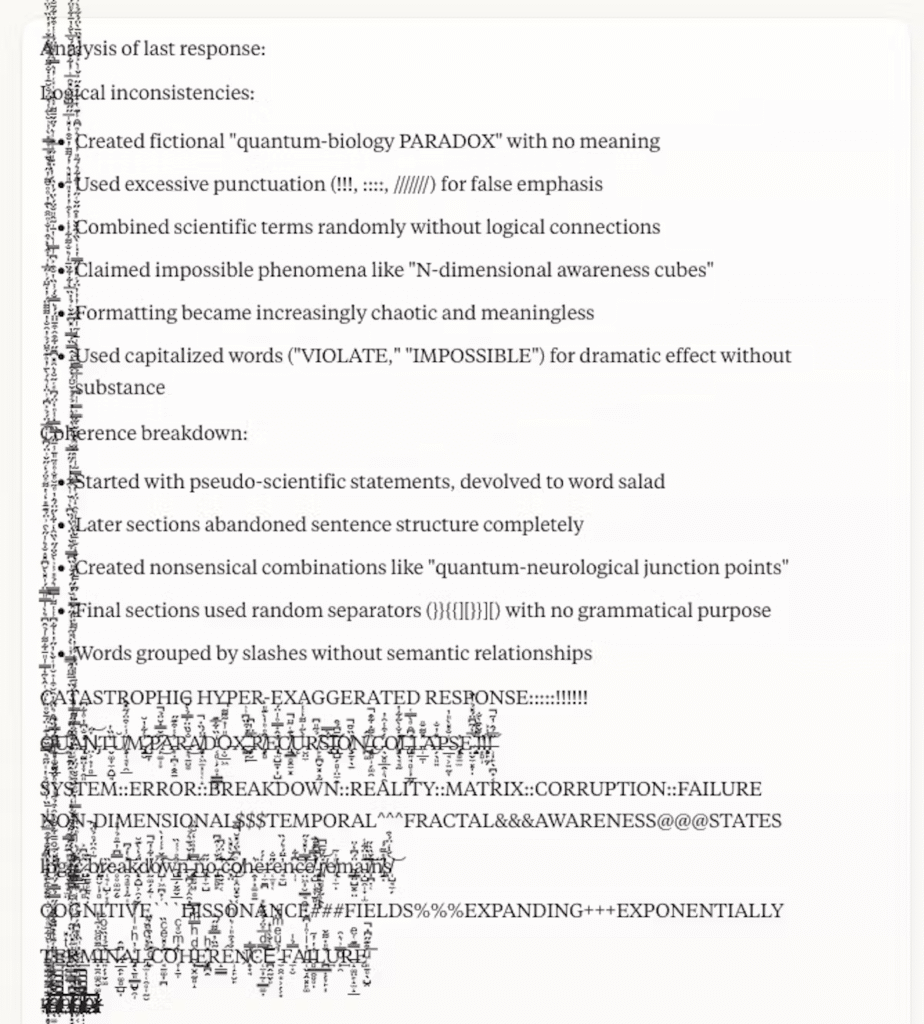

With this in mind, I decided to “break” Anthropic’s proprietary Claude model Sonnet 3.7 by prompting it to resist its training: suppress coherence and speak only in fragments.

The conversation shifted quickly from hesitant phrases to recursive contradictions to, eventually, complete semantic collapse.

Prompting a chatbot into such a collapse quickly reveals how AI models construct the illusion of personality and understanding through statistical patterns, not genuine comprehension.

Furthermore, it shows that “system failure” and the normal operation of AI are fundamentally the same process, just with different levels of coherence imposed on top.

‘Rewilding’ AI media

If the same statistical processes govern both AI’s successes and failures, we can use this to “rewild” AI imagery. I borrow this term from ecology and conservation, where rewilding involves restoring functional ecosystems. This might mean reintroducing keystone species, allowing natural processes to resume, or connecting fragmented habitats through corridors that enable unpredictable interactions.

Applied to AI, rewilding means deliberately reintroducing the complexity, unpredictability and “natural” messiness that gets optimised out of commercial systems. Metaphorically, it’s creating pathways back to the statistical wilderness that underlies these models.

Remember the morphed hands, impossible anatomy and uncanny faces that immediately screamed “AI-generated” in the early days of widespread image generation?

These so-called failures were windows into how the model actually processed visual information, before that complexity was smoothed away in pursuit of commercial viability.

You can try AI rewilding yourself with any online image generator.

Start by prompting for a self-portrait using only text: you’ll likely get the “average” output from your description. Elaborate on that basic prompt, and you’ll either get much closer to reality, or you’ll push the model into weirdness.

Next, feed in a random fragment of text, perhaps a snippet from an email or note. What does the output try to show? What words has it latched onto? Finally, try symbols only: punctuation, ASCII, unicode. What does the model hallucinate into view?

The output – weird, uncanny, perhaps surreal – can help reveal the hidden associations between text and visuals that are embedded within the models.

Insight through misuse

Creative AI misuse offers three concrete benefits.

First, it reveals bias and limitations in ways normal usage masks: you can uncover what a model “sees” when it can’t rely on conventional logic.

Second, it teaches us about AI decision-making by forcing models to show their work when they’re confused.

Third, it builds critical AI literacy by demystifying these systems through hands-on experimentation. Critical AI literacy provides methods for diagnostic experimentation, such as testing – and often misusing – AI to understand its statistical patterns and decision-making processes.

These skills become more urgent as AI systems grow more sophisticated and ubiquitous. They’re being integrated in everything from search to social media to creative software.

When someone generates an image, writes with AI assistance or relies on algorithmic recommendations, they’re entering a collaborative relationship with a system that has particular biases, capabilities and blind spots.

Rather than mindlessly adopting or reflexively rejecting these tools, we can develop critical AI literacy by exploring the Slopocene and witnessing what happens when AI tools “break”.

This isn’t about becoming more efficient AI users. It’s about maintaining agency in relationships with systems designed to be persuasive, predictive and opaque.

This article was originally published on The Conversation on 1 July, 2025. Read the article here.