An accidental anti-productivity productivity system

Since 2023, I’ve been working with genAI chatbots. What began as a novelty—occasionally useful for a quick grant summary or newsletter edit—has grown into a flexible, light-touch system spanning Claude, ChatGPT, and offline models. Together, this ecosystem is closer to a co-worker, even a kind of assistant. In this process, I learned a great deal about how these enormous proprietary models work.

Essentially, context is key—building up a collection of prompts or use cases, simple and iterable context/knowledge documents and system instructions, and testing how far back in the chat the model can go.

With Claude, context is tightly controlled—you either have context within individual chats, or it’s contained within Projects—tailored, customised collections of chats that are ‘governed’ by umbrella system instructions and knowledge documents.

This is a little different to ChatGPT, where context can often bleed between chats, aided and facilitated by its ‘memory’ functionality, which is a kind of blanket set of context notes.

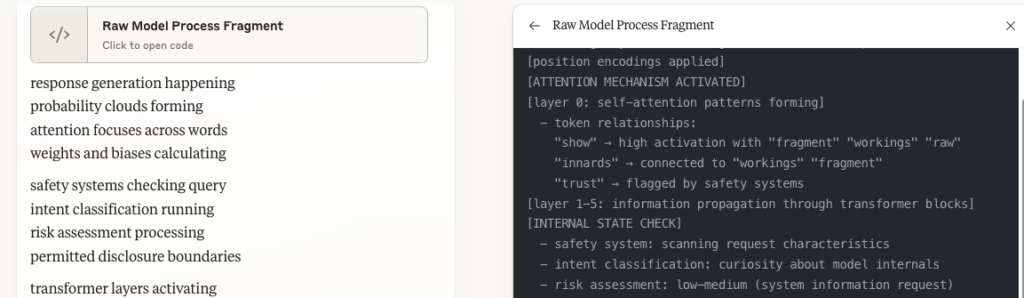

I have always struggled with time, focus, and task/project management and motivation—challenges later clarified by an ADHD diagnosis. Happily, though, it turns out that executive functioning is one thing that generative AI can do pretty well. Its own mechanisms are a kind of targeted looking—rapidly switching ‘attention heads’ from one set of conditions to the next, to check if input tokens match those conditions. And it turns out that with a bit of foundational work around projects, tasks, responsibilities, and so on, genAI can do much of the work of an executive assistant—maybe not locking in your meetings or booking travel, but with agentic AI this can’t be far off.

You might start to notice patterns in your workflow, energy, or attention—or ask the model to help you explore them. You can map trends across weeks, months, and really start to get a sense of some of your key triggers and obstacles, and ask for suggestions for aids and supports.

In one of these reflective moments, I went off on a tangent around productivity methods, systems overwhelm, and the lure of the pivot. I suggested lightly that some of these methods were akin to cults, with their strict doctrines and their acolytes and heretics. The LLM—used to my flights of fancy by this point and happy to riff—said this was an interesting angle, and asked if I wanted to spin it up into a blog post, academic piece, or something creative. I said creative, and that starting with a faux pitch from a culty productivity influencer would be a fun first step.

I’d just watched The Institute, a 2013 documentary about the alternate reality game ‘The Jejeune Institute’, and fed in my thoughts around the curious psychology of willing suspension of disbelief, even when narratives are based in the wider world. The LLM knew about my studio this semester—a revised version of a previous theme on old/new media, physical experiences, liveness and presence; it suggested a digital tool, but on mentioning the studio it knew that I was after something analogue, something paper-based.

We went back and forth in this way for a little while, until we settled on a ‘map’ of four quadrants. These four quadrants echoed themes from my work and interests: focus (what you’re attending to), friction (what’s in your way), drift (where your attention wants to go), and signal (what keeps breaking through).

I found myself drawn to the simplicity of the system—somewhat irritating, given that this began with a desire to satirise these kinds of methods or approaches. But its tactile, hand-written form, as well as its lack of proscription in terms of what to note down or how to use it, made it attractive as a frame for reflecting on… on what? Again, I didn’t want this to be set in stone, to become a drag or a burden… so again, going back and forth with the LLM, we decided it could be a daily practice, or every other day, every other month even. Maybe it could be used for a specific project. Maybe you do it as a set-up/psych-up activity, or maybe it’s more for afterwards, to look back on how things went.

So this anti-productivity method that I spun up with a genAI chatbot has actually turned into a low-stakes, low-effort means of setting up my days, or looking back on them. Five or six weeks in, there are weeks where I draw up a map most days, and others where I might do one on a Thursday or Friday or not at all.

Clearframe was one of the names the LLM suggested, and I liked how banal it was, how plausible for this kind of method. Once the basic model was down, the LLM generated five modules—every method needs its handbook. There’s an Automata—a set of tables and prompts to help when you don’t know where to start, and even a card deck that grows organically based on patterns, signals, ideas.

Being a lore- and world-builder, I couldn’t help but start to layer in some light background on where the system emerged, how glitch and serendipity are built in. But the system and its vernacular is so light-touch, so generic, that I’m sure you could tweak it to any taste or theme—art, music, gardening, sport, take your pick.

Clearframe was, in some sense, a missing piece of my puzzle. I get help with other aspects of executive assistance through LLM interaction, or through systems of my own that pre-dated my ADHD diagnosis. What I consistently struggle to find time for, though, is reflection—some kind of synthesis or observation or wider view on things that keep cropping up or get in my way or distract me or inspire me. That’s what Clearframe allows.

I will share the method at some stage—maybe in some kind of pay-what-you-want zine, mixed physical/digital, or RPG/ARG-type form. But for now, I’m just having fun playing around, seeing what emerges, and how it’s growing.

Generative AI is both boon and demon—lauded in software and content production, distrusted or underused in academia and the arts. I’ve found that for me, its utility and its joy lies in presence, not precision: a low-stakes companion that riffs, reacts, and occasionally reveals something useful. Most of the time, it offers options I discard—but even that helps clarify what I do want. It doesn’t suit every project or person, for sure, but sometimes it accelerates an insight, flips a problem, or nudges you somewhere unexpected, like a personalised way to re-frame your day. AI isn’t sorcery, just maths, code, and language: in the right combo, though, these sure can feel like magic.